Here’s one example of why you might want to hire me to help organize your exhibition, programming, or other content. If you call me in advance of your opening, I can help you catch unfortunate adjacencies like this one:

Here’s one example of why you might want to hire me to help organize your exhibition, programming, or other content. If you call me in advance of your opening, I can help you catch unfortunate adjacencies like this one:

In response to a call for content for a book titled Hack(ing) School(ing), I wrote an article on how we should replace middle- and high-school history content standards with helping students to develop curatorial skills. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the topic. Check out the post at my more academic blog, The Clutter Museum.

Last month, I kicked off a series of posts about museums and emerging technologies, and specifically the actual and potential interplay of technologies across educational sectors (K-12, museums, and higher ed)—and how museums might make the most of these intersections. In this post I’m going to consider augmented reality—a technology the New Media Consortium forecasts will be more widely adopted in museum education and interpretation within the next couple years, and within K-12 education within four to five years.

The NMC’s 2011 Horizon Report for museums explains augmented reality:

Augmented reality applications can either be marker- based, which means that the camera must perceive a specific visual cue in order for the software to call up the correct information, or markerless. Markerless applications use positional data, such as a mobile’s GPS and compass, or image recognition, where input to the camera is compared against a library of images to find a match. Markerless applications have wider applicability since they function anywhere without the need for special labeling or supplemental reference points. Layar (go.nmc.org/rfomi) has been a leader in this space with augmented reality applications for the Android and iPhone platforms. Layar Vision is a markerless application of AR that makes it easy to develop apps that can recognize real world objects and overlay information on top of them.

Museums are pretty far ahead of their K-16 colleagues in implementing this version of augmented reality. Some examples:

Once downloaded, you need only point your phone at a targeted marker for [James] May to appear in all his three-dimensional glory on the screen of your smartphone or tablet. Your position in relation to the marker directly effects Mr. May’s. So, if you were to walk 180 degree around it, you would see the opposite of Mr. May’s body. Through nine installments in the gallery, he will talk to you and move just as if he were there in the flesh, your own diminutive downloadable docent!

You can download the markers for the exhibit (PDF) to watch May’s performance from anywhere in the world.

One of the most exciting museum AR projects to date didn’t originate with the museum itself. Rather, two artists made a guerrilla art show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, superimposing new artwork onto the walls of MoMA’s galleries through Layar, and even adding an additional virtual floor onto the museum to accommodate the new pieces.

The HistoryPin app draws on HistoryPin’s crowdsourced project to put historical photos on the map. Using the app, you can superimpose historical photos onto the present-day landscape. History museums and archives could use this simple AR platform to share their collections. Each photo that your institution adds to the HistoryPin map includes a link to your institution’s HistoryPin “channel,” where you can talk up your museum, its exhibits, and its collections. (Check out the U.S. National Archives channel for a great use of this platform.) You can also create tours, as the National Archives has done with the civil rights-era March on Washington. (You might also check out Tagwhat, a similar app that allows people to build “interactive stories” that include photos and video.)

These AR applications are targeted largely at adults, but that doesn’t mean we have to leave kids out of the fun. I’m a fan of traditional sand-and-water tables, but this use of the Kinect platform at UC Davis is pretty damn cool. Imagine all the ways science centers might deploy this technology–what about demonstrating the possible shifts of rivers, oceans, lakes, and terrain due to climate change?

I frequently hear museum administrators say they can’t adopt these technologies because their staff doesn’t have the expertise—or the time to develop that expertise. And I get that–we’re all very busy trying to stay afloat in an underfunded cultural sector. However, just because we lack the time or expertise doesn’t mean we can’t bring someone on board who either has that expertise or–even better–wants to acquire it.

My solution: find a student intern who wants to learn about some aspect of museums, and then encourage her to find new applications for these technologies in the department in which she’s interning.

So, for example, you can hire a collections intern and immerse her in conservation work—by which I mean you both guide her through the process of conserving an artifact or a small collection of artifacts, but also impress on her the broader contours of, and challenges facing, the field. You might emphasize that some objects are too fragile or unstable to be put on exhibit, lament that only a small portion of the museum’s collection will ever be displayed, or express visitors’ frustrations that they can’t see the back of some of the textiles currently on exhibit. You would then challenge the student to use augmented reality technology to make the collections more accessible to visitors. Depending on the length of the internship, you could either have the student actually deploy a beta version of your AR project or have her write a white paper on the various AR technologies that might reasonably be used by the museum, recommend one, and then outline how to deploy an AR project for the next intern. Alternately, depending on the student’s interests, you could ask the student to research opportunities for grants, and then draft a grant proposal.

It’s win-win: Your intern gets a sense of collections work and new technologies, your museum learns about how it might deploy AR, and your intern has a project–either an AR project, white paper, or grant proposal–to show to future employers.

I’m putting this into practice myself in the fall, when undergraduate and graduate students in my new Digital History course will research AR platforms and create a walking tour of downtown Boise that uses AR to give visitors a glimpse of the historic city. (I’ll let you know how that goes.)

Of course, it’s easy to get caught up in the oooh! shiny! factor of new technologies, and AR implementation definitely presents such a peril. If we’re not careful, it could become just another gimmick instead of truly augmented educational programs and projects. Margaret Schavemaker points out that it’s important to foreground museum visitors’ authentic encounters:

Of course one can denounce “paratouring” — or, in terms of AR, “pARatouring” — as a distraction from what the tour is really about, namely, mediating knowledge and enhancing visitor experience both inside and outside the museum. This is a risk, and we should take care that it does not obstruct the actual encounter with the museum, collection or exhibition.

As you can see by some of the examples—particularly those platforms that allow anyone to contribute, such as Tagwhat and HistoryPin—museums can test the waters of augmented reality without breaking the bank. Whether you budget a bit of time for your staff to upload photos to HistoryPin or hire an intern to explore Layar or Aurasma, your institution need not invest a lot of money into exploring this virtual frontier.

How might your institution use AR?

If you want to read about additional opportunities for museums to deploy AR, you can download Areti Damala’s dissertation, “Interaction Design and Evaluation of Mobile Guides for the Museum Visit: A Case Study in Multimedia and Mobile Augmented Reality.” (PDF)

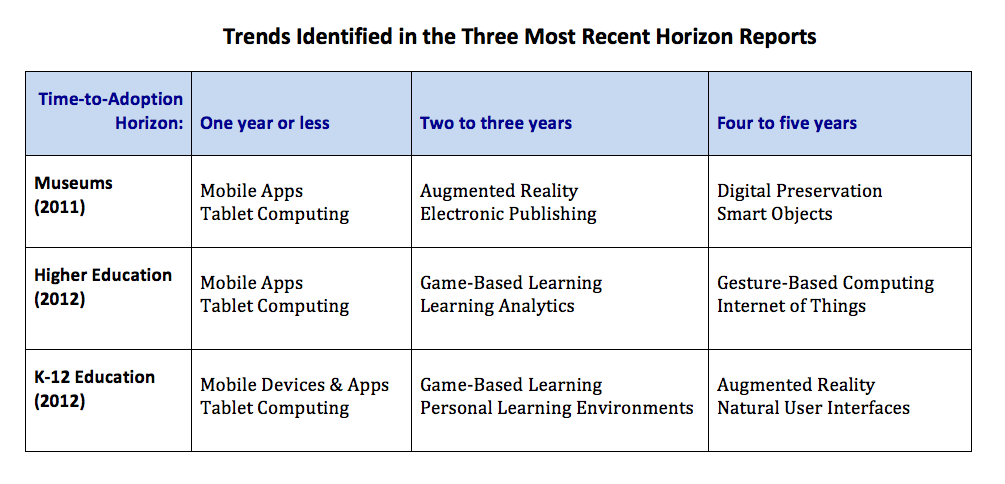

In collaboration with its various partners, the New Media Consortium (NMC) each year publishes three versions of its Horizon Report: one each for K-12 education, higher education, and museum education and interpretation. Each publication forecasts trends in technology in these respective sectors.

The reports always generate thoughtful discussion among practitioners in these fields, and I’ve noticed that of particular interest to many folks are the technologies forecast to be three to five years out. That said, I haven’t heard much conversation within each field about the others’ reports. This is an odd gap in the discourse about technology, as formal and informal education influence one another in dynamic ways. With mobile devices becoming increasingly ubiquitous across socioeconomic classes, the lines between informal and formal educational spaces are blurred, sometimes beyond recognition or restoration.

I’ve created a table comparing the most recent NMC technological forecasts for museums, higher ed, and K-12 education. Take a look:

Click image to enlarge. Note: I received a pre-release copy of the 2012 K-12 Horizon Report. It’s not yet available in its entirety to the public,but those of us with pre-release copies are encouraged to write about it.

Click image to enlarge. Note: I received a pre-release copy of the 2012 K-12 Horizon Report. It’s not yet available in its entirety to the public,but those of us with pre-release copies are encouraged to write about it.

I don’t think it’s a surprise to anyone within these educational sectors that mobile apps and tablet computing are arriving on the scene. Students, faculty, museum visitors, and museum staff frequently carry smart phones that allow them to access all kinds of information at a moment’s notice. Nor do I think it’s particularly surprising to suggest game-based learning and PLEs are hot in K-12, or that games and learning analytics are going to take off in colleges and universities. However, the rest of the technologies on this chart are, while certainly not controversial, more open to debate and speculation.

I’d like to take some time, then, to reflect on the relationships among technologies such as augmented reality, games, analytics, PLEs, digital preservation, smart objects, and gesture-based computing, and consider how students’ and visitors’ use of these technologies might be brought to bear within museum exhibitions, programming, and digital outreach.

I’ll be publishing a series of posts on the utility of, and the possibilities inherent in, these technologies—taken individually, and as a constellation—across sectors.

But first, some definitions, pulled directly from the reports:

Augmented reality is “the layering of information over 3D space” to produce “a new experience of the world,” a “blended reality” (Museums, p. 18).

Game-based learning encompasses a broad spectrum of “serious play,” including “games that are goal-oriented; social game environments; non-digital games that are easy to construct and play; games developed expressly for education; and commercial games that lend themselves to refining team and group skills. Role-playing, collaborative problem solving, and other forms of simulated experiences are recognized for having broad applicability across a wide range of disciplines” (Higher Ed, p. 18).

“Learning analytics refers to the interpretation of a wide range of data produced by and gathered on behalf of students in order to assess academic progress, predict future performance, and spot potential issues” (Higher Ed, p. 22).

Personal learning environments (PLEs) cross the borders between formal and informal education in their support of “self-directed and group-based learning, designed around each user’s goals, with great capacity for flexibility and customization. The term has. . .crystallized around the personal collections of tools and resources a person assembles to support their own learning” (K-12, p. 24).

“Digital preservation refers to the conservation of important objects, artifacts, and documents that exist in digital form.” Software and hardware can become obsolete very quickly, and museums that collect electronic media are going to find such the management of such artifacts and resources increasingly complex. “Digital preservation calls for a new type of conservationist with skills that span hardware technologies, file structures and formats, storage media, electronic processors and chips, and more, blending the training of an electrical engineer with the skills of an inventor and a computer scientist” (Museums, pp. 26-28).

Gesture-based computing and natural user interfaces allow users to engage in virtual activities with motions and movements similar to what they would use in the real world, manipulating content intuitively” (Higher Ed, p. 27; K-12, p. 33).

“The Internet of Things has become a sort of shorthand for network-aware smart objects that connect the physical world with the world of information. A smart object has four key attributes: it is small, and thus easy to attach to almost anything; it has a unique identifier; it has a small store of data or information; and it has a way to communicate that information to an external device on demand” (Higher Ed, p. 30).

I expect the first of these posts to be up later this week. I’ll link to each post in the series as they become available.

While researching local history, one of my students recently came across an old newspaper article she thought I’d find amusing. Titled “Old Scenes Take Form At Museum,” it was a piece on a new exhibit opening in the state history museum.

I do indeed find museum history interesting, so I was eager to see how the exhibit was described, what motivated the museum to put it up, and to compare it with the exhibits in the museum today so that I can get a better sense of how the museum’s exhibition philosophies and priorities have shifted.

You can see where this is going, right?

The exhibit featured in the newspaper is still up today, and from the description in the article, it appears it hasn’t changed at all.

The newspaper article was published in the early 1960s.

My point in writing this post is not to shame or embarrass the museum in question. (It certainly isn’t alone in having permanent exhibits that are, well, permanent.) As with many state history programs—and, I’m guessing, like many such programs in politically conservative states, where education tends not to be funded as fully as it might be elsewhere—it’s clear even to the casual visitor that the museum doesn’t have the money to mount new exhibits on a regular basis.

Still, it’s important to point out the liabilities of such an approach to exhibitions to underscore the importance of keeping up-to-date with museum theory and practice.

First, it’s not good when visitors say about your museum—as did the students, aged 20-50, I took to this museum last month—”It hasn’t changed since I was a kid.” The number of visitors who appreciate the nostalgia factor is likely to be far smaller than those who would like to see a new exhibit. Late last year, Reach Advisors delved into their databases to determine what visitors’ attitudes are to changing exhibits—and whether these attitudes differ among museum members, frequent visitors, and occasional visitors. Among their findings:

Changing exhibitions does not necessarily mean huge costs, though costs are certainly a factor. Of the written-in comments we examined asking for more changing exhibitions, none referred to what we call “blockbuster” exhibitions. Some suggested small changes to liven things up. Change might be a “science in the news” area, which changes on a weekly basis but would not necessarily meet design standards for a longer-lasting exhibition. Change can be delving into the permanent collection and highlighting an artist, or a local history topic, and featuring those items through a new lens (a tactic deployed by many museums during these rough economic times). Change doesn’t mean an expensive line item, and it doesn’t mean changing over the entire museum every six weeks, though it does mean a commitment of some funds and considerable time.

One of the most commonly asked questions on humanities and arts grant applications today seems to be some variation of, “What’s innovative about your project?” A museum might be able to find a grant writer who could answer that question relatively persuasively about a proposed exhibition redevelopment, but if I were on a grant proposal review committee—and I have been—I would be looking for evidence that the museum has dabbled in whatever brand of innovation its staff wishes to implement. In the case of this particular museum, if I saw that most of the exhibits were 30, 40, or 50 years old, I would wonder about the museum’s capacity to implement best practices in museum education and exhibition—simply because I don’t see many signs in the current exhibits that the museum is even interested in experimenting with, say, interactivity or with exhibit panels of fewer than 300 to 500 words.

Let’s say this museum knows it should implement a new degree of interactivity but it hasn’t. Because authentic artifacts are the traditional history museum’s stock-in-trade, incorporating interactivity may at first seem a challenge because visitors can’t touch the artifacts the way they can interact with objects and manipulatives in a science center or children’s museum. Furthermore, if the exhibition development and education staff of a history museum hasn’t been provided quality opportunities for professional development—and I don’t know if that’s the case with this particular museum, but the museum’s exhibits do not reflect the at least last 20 years or so of theory and practice—then they might not be able to think beyond expensive replicas and the sometimes complex “recipes” for fabrication designed by science centers like the Exploratorium. Once we can force ourselves to think beyond video kiosks, replicas, and dynamic science interactives, we find many possible baby steps toward interactivity or visitor participation. It’s easy to add a simple paper-and-pen or token-based polling system for visitors, create laminated cards or brochures that offer alternative tours through the museum based on individual visitors’ interests, or affix QR codes to exhibit labels to direct visitors to more in-depth content on the museum’s website or to additional photographs of the object from angles that aren’t visible to the visitor.

Interactivity can be simple and inexpensive to integrate into an exhibit, and much information is available freely online about how to successfully include interactive components in an exhibit. There’s no longer any good reason a museum hasn’t adopted such techniques, and it doesn’t make sense for a museum to ask for funding for a new, innovatively interactive exhibition if it hasn’t shown interest or capacity in more basic interactive techniques.

Although museum professionals know that in most museums only a small percentage of artifacts ever see the exhibition floor, my sense is that few donors to local history museums understand their treasures likely will remain in storage in perpetuity. Donors who wish to see their gifts on display during their lifetimes may be dissuaded by decades-old exhibits or by temporary exhibits not drawn from the museum’s collection. In addition, speaking for myself, I’d be unlikely to donate my family’s beloved heirlooms to a museum if the institution lacked the creativity and wherewithal to interpret artifacts in ways that challenge visitors to think critically and creatively.

Let’s consider a few ways to update this exhibit relatively inexpensively and thus gain some respect in the eyes of visitors, current and prospective donors, and even funders.

A wringer washer in Wyoming. Image by arbyreed, and used under a Creative Commons license.

First, a description. The “old scenes” mentioned in the newspaper article comprise a kitchen and porch exhibit whose central feature appears to be laundry. I haven’t paid attention to the exhibit lately, but if memory serves, there is a wringer washer, soap containers, and some other household goods arrayed on a porch. The article describes it thus: “The porch display. . .will include an old hand-crank clothes washer, ice-box refrigerator, rocking chairs and a stack of wood.”

The exhibit depicts, in other words, a tiny slice of domestic life at the turn of the last century. My reading of it is as cute and nostalgic in a way that makes me uneasy because the woman who would be using the objects displayed in the kitchen and on the porch is absent; her labor becomes invisible. So, in this scenario, let’s find a way to make that woman and her labor visible to the visitor.

Assuming visitors can get network reception inside the museum’s building, I recommend adding multimedia content accessible via smartphone, 3G or 4G tablet, or, if the museum is equipped with public wifi, a wireless device like an iPod Touch or wifi iPad. Having such content available on devices a visitor brings with her, or even on a device that can be checked out from the front desk, means that the museum won’t need to buy, maintain, and update a bulky and expensive audio or video kiosk. This content might be accessible through a QR code or simply a URL printed at the bottom of the exhibit’s interpretive panel.

Audio content might include the voice of a woman talking about how tired she is after using all these devices or telling a story about how her curious toddler stuck his hand into the wringer when her attention was directed toward another one of her children, and she cranked the handle (audio of child screaming or crying), and the doctor had to be called to examine the child’s hand. Alternately, the printed URL might take the user to a YouTube video of someone using a hand-cranked washer:

In an underfunded museum such as this one, audio content could be created by interns who undertake research into the use of such machines, then are given free range with Audacity or another free or low-cost audio editing program. Interns also could seek out such video footage of an antique washer, such as I’ve posted above, and embed it onto mobile-friendly pages on the museum’s website. (Of course, best practice for any institution would be to include a link to a transcript of the audio for deaf visitors and a description of the video for blind visitors.)

Or we could tell a different kind of story. This is, after all, a museum with a quarter million objects in its collection, so it has plenty of artifacts it could be exhibiting. Perhaps we see the open porch at a moment of transition; it’s being enclosed to make a laundry room, and the woman has set her old hand-cranked washer and wringer out in the yard to make way for her new machine, which features an electric agitator. Audio or textual content could describe the woman’s feelings about the new machine at the moment of its arrival, as well as showcase her ambivalence a few months down the road, when she complains about constantly having to repair it, or when she expresses the belief that it’s too rough on her family’s clothes, wearing them out prematurely.

In this scenario, collections and education staff could establish a schedule whereby the laundry machines and interpretive content (text or audio) are updated every few months. Visitors could play a game, made with magnets and laminated photos of old laundry machines, in which they try to place the laundry machines in the correct chronological order.

Or, of course, we could abandon laundry altogether. It isn’t, after all, the sexiest subject. Moving away from laundry, however, doesn’t have to mean a complete (and costly) exhibit renovation. The relative openness of the porch exhibit “stage” lends itself to any number of scenes in a way that, say, the built-in cabinets and framed windows of the restored formal dining room in an adjacent exhibit do not. The museum could tell any number of stories about race, class, age, gender, leisure, and labor.

And need I mention that it’s best practice to rotate artifacts? Changing exhibits allow objects relief from light, vibration, and other damaging phenomena.

I’d love to hear your own stories of

I’m also eager to hear what solutions you’d propose to the particular challenge I’ve shared in this post. What advice would you give the museum staff?

A version of this post also appears at The Clutter Museum.

Because I’m one of only two faculty in my department whose specialty is officially “public history”—mind you, we all practice one form of it or another, but I have been anointed by my position description—pretty much all the applications for admission to my university’s Master’s in Applied Historical Research program come across my desk. Usually I just write a few notes explaining why I’m recommending we admit the candidate, admit her provisionally, or decline to admit her, and then that’s the last I see of the application. I also don’t get to see my colleagues’ comments on the application, as that might unduly bias me.

Occasionally, however, an application comes back to me when individual faculty make conflicting recommendations about admission. So, for example, I might say we should admit someone, but two or three of my fellow faculty recommend the opposite. In many departments, a majority “no” vote might be the end of the line for an application, but our graduate program director gives me (or anyone else whose vote differs, I’m assuming) the opportunity to reconsider the application, to change my vote or take a stand or something in between.

At such moments, I get to see the admissions recommendations and, more importantly, the comments of my fellow evaluators. And often I’m in complete agreement with what they’re saying about the application, but I still want to recommend the opposite of what they do.

I’m not sure why, but it took me a year and a half in the department to realize that our occasionally differing visions about who should be admitted to the program stem from our–wait for it–differing visions about the program’s capabilities and mission.

My friends, we lack collective clarity.*

See, we have two programs: a traditional M.A. in history, and the M.A.H.R. The department’s web page describes the programs using almost exactly the same language, differentiating between the two only by saying the M.A. will prepare students for work in academic settings at all levels (by which I assume we mean high school teaching or the occasional adjunct gig) and the M.A.H.R. prepares students for careers outside academic settings. Programmatically, the degree requirements differ very little, with M.A.H.R. students taking one additional seminar in public history—but when I taught that course last spring, there were several M.A. students in it, too. The M.A.H.R. students can substitute “skills” courses (like GIS or video editing) for the foreign language courses required of the M.A. students. The M.A.H.R. students are also allowed, and encouraged, to take more internship credits.

If you’ve been around the humanities graduate program block lately, maybe you’re reading this as I do: the M.A.H.R. program is about helping students take very specific steps toward getting jobs. The M.A. program. . .maybe not so much. I don’t work with the M.A. students much, so I’m not sure what they want out of the program, but the M.A.H.R. students often have very specific goals: to open a historical consulting firm, to go into museum exhibit development, to make a documentary film, to apprentice themselves in a historic preservation office.

I wrote a memo to the graduate program coordinator in which I asked these questions (and provided my own tentative answers):

Here’s the thing: I read a lot of mediocre writing in those applications, from both M.A. and M.A.H.R. applicants. Many of the objections from my colleagues stem from applicants’ bad writing or poor research skills. And in my own classes, I’m a pretty unforgiving taskmaster when it comes to writing. So I’m not suggesting that we lower to the admissions bar for M.A.H.R. applicants. Yet maybe we need to acknowledge that public historians’ work embraces a huge spectrum; some public historians might find themselves addressing K-6 students, while others work primarily with policymakers. On the job, some will rarely write anything longer than an exhibit label. Others will need to write eloquently in grant proposals. Many will need to do both.

I suspect that many of the applicants who can’t write a good enough academic essay to be admitted to a traditional academic programs can still engage in critical and creative thought–it’s just that the essay isn’t the best way for them to exhibit these skills. Someone who is a good fit for our M.A. program might not be a good fit for the M.A.H.R. program, and vice versa. I suspect we faculty have been treating applicants as if they’re applying to the same program.

The grad program coordinator told me to bring my questions and concerns to the faculty at a department meeting. Our faculty meetings are relatively fleet things, thank goodness, but it also means I need to find a way to encourage people to either (a) coalesce around a unified vision in, oh, 10-15 minutes or (b) reflect on what they think the difference between the two programs should be and share their individual visions with me before the next meeting.

Of course, before I do that, I’d like some information from other programs. I’ll be scouring departmental web pages and perhaps contacting some folks, but in the meantime, here’s what I’d like from you, dear readers:

If you teach in, or pursued a degree within, a humanities or social science department that offers to graduate students an “academic” track and a “practical” or “non-academic career” track (e.g. history and public history), how do you differentiate between applicants to the two programs? Do you require essays or something else? Do you require interviews? Do you expect applicants to propose specific projects? Do you ask recommenders to comment on the applicants’ career potential instead of just their academic performance? How can you tell which applicants might be a better fit for one degree track over another?

Please share your experiences and thoughts in the comments. I know some folks like to maintain their anonymity in such forums as this one; if that’s the case, you can either obfuscate a few details, comment anonymously, or e-mail me privately at trillwing -at- gmail -dot- com.

Many thanks!

* . . .in an academic department. A stunning revelation, I know.

Photo by vlasta2, and used under a Creative Commons license.

I'm a museum therapist of sorts. . . I listen, question, provoke (gently). Remember when your museum work was rewarding, meaningful, and fun? I help my individual and institutional clients revive that magical blend of curiosity, learning, and sharing.

(Note: not a real therapist.)

Like us on Facebook

Follow me on Twitter

Add me to your circles on Google+